With Interior Lives, Przemek Pyszczek projects us into his personal creative dimension, into a landscape determined by elements that generate a kind of contrast, or rather a dualism between opposing forces and circumstances. The walls of the gallery lose their merely structural function and become the ideal façade of a house where the “paintings/windows” open to an idea of elsewhere. These works are membranes between two dimensions, Cartesian axes that establish a “this side” and a “beyond.” The iron structures resting on top of the canvases and a characteristic feature of Pyszczek’s work, in the new series no longer converse with geometrically defined backgrounds, rather the circular silhouettes and diagonal segments, echoing the typical gratings of Polish city centers, stand out in contrast on surfaces treated with a fluid paint that flows over the support and blends following an indeterminate stream, sometimes even leaving portions of rough fabric, discontinuities due to chance and the unpredictable water repellency of the canvas. A movement that in this case acts on a microscopic level, but has an unfathomable universal echo. The visual manifestation of this flow is reminiscent of the shapes that sea water draws when it breaks on sand, the way rivers, lakes, and continents have formed over millennia by intervening in the morphology of the earth, and the conformation of stars and galaxies that we observe when we look at deep space photography. A minimal gesture that contrasts with the artificiality of the grid by deconstructing reality and making us reflect on the nature of the creative act in relation to an immanent conception of the divine.

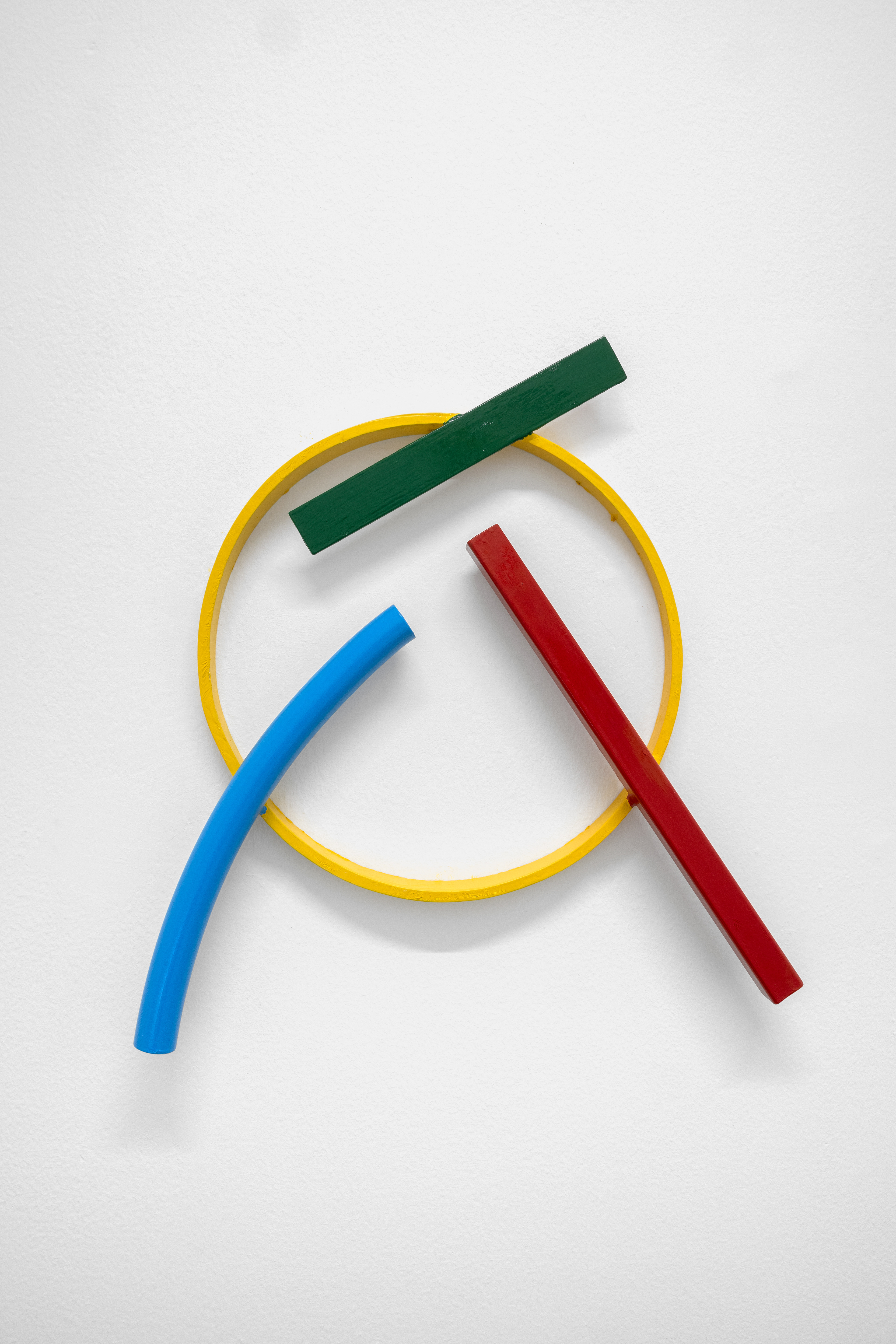

The intent to reconstruct an abstract landscape that retains traces of reality and then opens up to a contemplative dimension is also present in the sculptural works scattered on the gallery floor and walls. The compositions created through the assembly of painted metal tubes hark back to children’s playgrounds that were widespread in the USSR and its satellite states, and an integral part of the urban landscape in the 1970s and 1980s. These playground structures, which still exist today, can be found in almost every public garden in large Eastern European cities - and are generally found outside schools or near churches or high-density streets. As standardized and almost “mass-produced” products for their construction, there was a tendency to follow repetitive patterns and designs that went into articulating swings, rockers, rockets, traffic circles, or bridges. The loss of their original functionality in favor of the adoption of a sculptural form that leads back to a certain constructivism on the one hand and to the modus of minimal sculpture on the other makes them appear as something else. These works are a reminder of a childhood he never lived (the artist was born in Poland but grew up in Canada, returning to his homeland only around the age of twenty) and imagined with each weld, each overlapping layer of colored paint, but they are also a broader reflection regarding the failure of certain social and political structures. Thus, an intrinsic movement returns that leads to a continuous shifting between poles, the individual and the collective, the inside and the outside, the micro and the macrocosm.

-Text by Maria Villa