Please visit GalerieDerouillon.com for further information

For as long as I can remember, upon visiting my grandparents in the heart of the elegant Żoliborz district in north Warsaw, I would take the opportunity to look at its famous modernist buildings, erected in the early 1960s at the instigation of the architect Halina Skibniewska. Those colourful, jutting balconies fascinated me; yellow, green or blue, sprinkled lightly across the concrete facades, like clouds hanging in a sombre sky.

Przemek Pyszczek, born in the mid-1980s in communist Poland, migrated with his parents to Winnipeg in Canada a few years before the fall of the Berlin wall. In the late 1990s, he returned to his home country for the first time, and discovered that most of those grey, concrete building facades, ubiquitous in the streets of his hometown, had been repainted with great sweeps of pastel colors and rounded shapes. Fascinated by modern socialist architecture, and by these “koloroblok” in particular — the long residential buildings that can be found all across Poland, from its working-class districts to its most affluent neighbourhoods, built according to a modular principle characterized by large, colourful, opaque glass panels — he started to document these recoloured colossuses, and to incorporate them into his work. He also began to turn his interest to the communist-era playgrounds that every Polish child remembers, its basic geometric shapes and cold metal decorated with bright primary colours. My grandparents’ building in Warsaw had one too, and we spent our summer afternoons there.

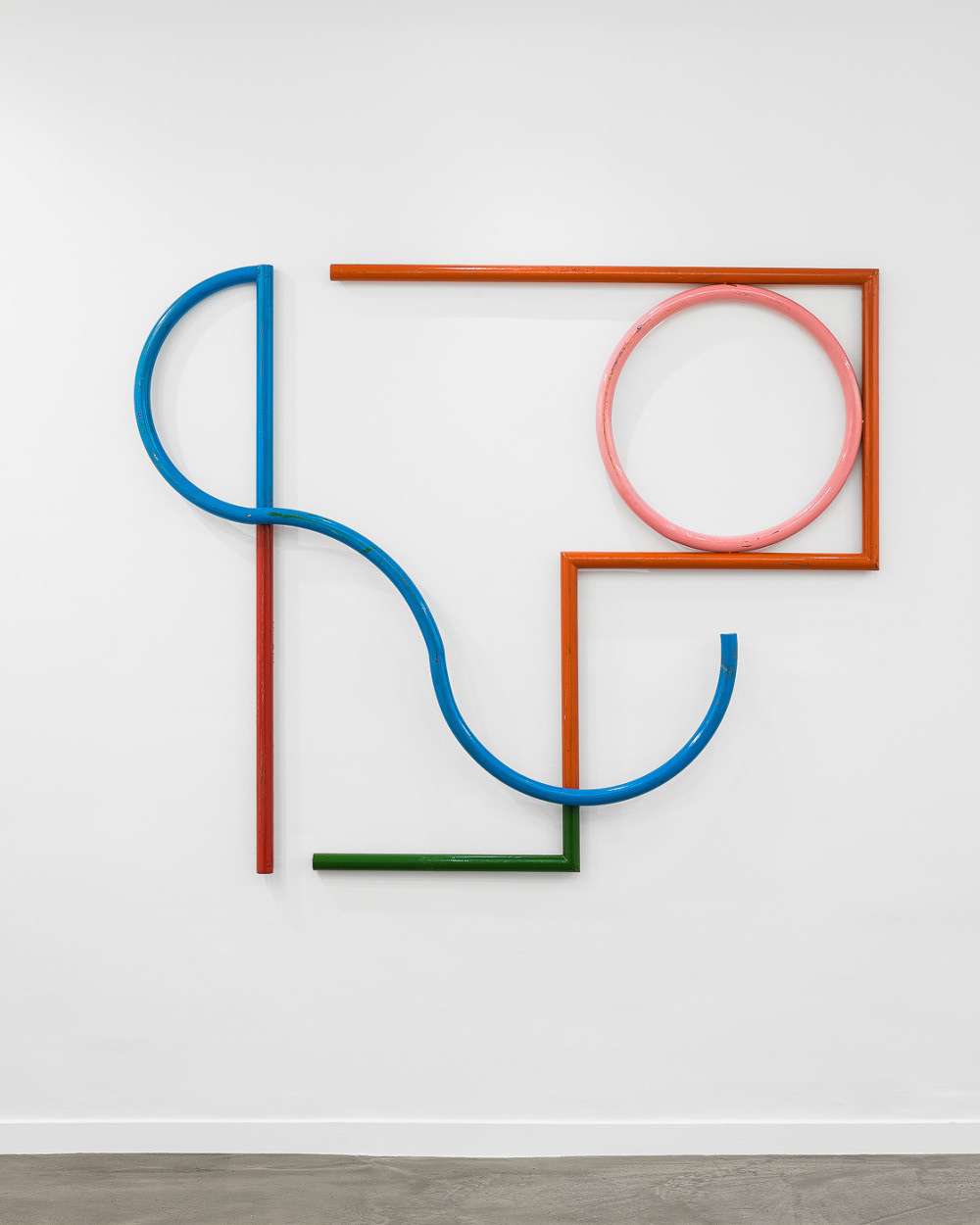

For his first solo exhibition in France, Przemek Pyszczek has produced a corpus of work that addresses his aesthetic and architectural research. Indeed, his bas-relief paintings reuse the same geometry of circles, squares or waves that decorate the balconies of Polish modernist buildings, and his sculptures manufactured by Polish metal factories are evocative of those colourful communist playgrounds. And yet, the artist seems to incorporate a certain distance vis-à-vis the architectural form, a distance that is made possible by the decontextualization he performs, from the street to the exhibition space. In their geometry, and in their use of bright, primary colours, his works also recall the constructivist compositions of the Polish sculptor Katarzyna Kobro who, in the interwar period and up until her death in 1951, produced a corpus of works of visionary architectural quality that instil harmony between the urban space and the observer’s experience, while at the same time advocating the idea that a work of art should not have a uniquely theoretical or aesthetic function, but also convey social criticism.

Although at first appearance, they seem quite direct, Although at first appearance, they seem quite direct, particularly in their spatial arrangements, Przemek Pyszczek’s works have in fact their share of ambiguity, and can even appear as confusing in terms of the true nature of the link between the vernacular object and its artistic representation. After all, does a building not, recoloured solely to make it more agreeable to look at, or even reconditioned to remove the traces of a past too cumbersome for a new Poland, then become a work of art, an artefact, a mental and aesthetic construct? What appears to bring it closer to the reality of its representation is the use of memory: a collective memory of an architecture representing a dissolute past, or a private memory of a fantasised place that the artist never grew up in — a recent exhibition of the artist, Sandomir, was incidentally named after the hometown of his father’s family. But Przemek Pyszczek’s approach, in the end, is less an ostalgie (neologism expressing a cultural nostalgia for the communist era) than a mixture of humour and pop culture, of reinterpretation and re-appropriation of the object. It is also evocative, not so much of the tale of a rediscovered childhood, than of the construction of a memoryscape, or a plural memory made of exile and immigration, of aesthetic exchanges and visual acculturation.

Martha Kirszenbaum, October 2017

Przemek Pyszczek, born in the mid-1980s in communist Poland, migrated with his parents to Winnipeg in Canada a few years before the fall of the Berlin wall. In the late 1990s, he returned to his home country for the first time, and discovered that most of those grey, concrete building facades, ubiquitous in the streets of his hometown, had been repainted with great sweeps of pastel colors and rounded shapes. Fascinated by modern socialist architecture, and by these “koloroblok” in particular — the long residential buildings that can be found all across Poland, from its working-class districts to its most affluent neighbourhoods, built according to a modular principle characterized by large, colourful, opaque glass panels — he started to document these recoloured colossuses, and to incorporate them into his work. He also began to turn his interest to the communist-era playgrounds that every Polish child remembers, its basic geometric shapes and cold metal decorated with bright primary colours. My grandparents’ building in Warsaw had one too, and we spent our summer afternoons there.

For his first solo exhibition in France, Przemek Pyszczek has produced a corpus of work that addresses his aesthetic and architectural research. Indeed, his bas-relief paintings reuse the same geometry of circles, squares or waves that decorate the balconies of Polish modernist buildings, and his sculptures manufactured by Polish metal factories are evocative of those colourful communist playgrounds. And yet, the artist seems to incorporate a certain distance vis-à-vis the architectural form, a distance that is made possible by the decontextualization he performs, from the street to the exhibition space. In their geometry, and in their use of bright, primary colours, his works also recall the constructivist compositions of the Polish sculptor Katarzyna Kobro who, in the interwar period and up until her death in 1951, produced a corpus of works of visionary architectural quality that instil harmony between the urban space and the observer’s experience, while at the same time advocating the idea that a work of art should not have a uniquely theoretical or aesthetic function, but also convey social criticism.

Although at first appearance, they seem quite direct, Although at first appearance, they seem quite direct, particularly in their spatial arrangements, Przemek Pyszczek’s works have in fact their share of ambiguity, and can even appear as confusing in terms of the true nature of the link between the vernacular object and its artistic representation. After all, does a building not, recoloured solely to make it more agreeable to look at, or even reconditioned to remove the traces of a past too cumbersome for a new Poland, then become a work of art, an artefact, a mental and aesthetic construct? What appears to bring it closer to the reality of its representation is the use of memory: a collective memory of an architecture representing a dissolute past, or a private memory of a fantasised place that the artist never grew up in — a recent exhibition of the artist, Sandomir, was incidentally named after the hometown of his father’s family. But Przemek Pyszczek’s approach, in the end, is less an ostalgie (neologism expressing a cultural nostalgia for the communist era) than a mixture of humour and pop culture, of reinterpretation and re-appropriation of the object. It is also evocative, not so much of the tale of a rediscovered childhood, than of the construction of a memoryscape, or a plural memory made of exile and immigration, of aesthetic exchanges and visual acculturation.

Martha Kirszenbaum, October 2017